The road to taking Italy was muddy, gruelling and littered with far more casualties than anticipated, and it took almost a full year of fighting from the start of ‘Operation Husky’ to the fall of Rome on 4 th June 1944 the achievement was more or less overlooked in the midst of celebrations of the success of D-Day (the Forces in Italy joked that they were seen as ‘D-Day dodgers in sunny Italy’). 105,000 Allied troops and 80,000 Germans fell in the battle. This was the most devastating phase of the whole campaign. They eventually bypassed the mountain and left the Polish Army, with some British assistance, to take the Germans from the 4 th Parachute Regiment prisoner. The Americans bombed the beautiful Christian site, destroying not only the ancient buildings but lots of precious cultural treasures, but ultimately achieved little. Monte Cassino, a sacred site with a monastery that had been taken over as a German stronghold, was the next obstacle. With a little help from friendly forces from all over the world, the Brits and Americans slowly pushed on. Interestingly, ‘Witness to World War Two’ notes that the Nisei-Americans, Japanese settlers in the US who had a very difficult time of it in the wake of Pearl Harbour, made several vital strikes on behalf of the Allies. Once again they met with fierce resistance, and although the beachheads were this time swiftly secured, they were soon under siege and grimly battling not to be pushed back into the sea. In January 1944, in ‘Operation Shingle’, the Allies landed at Anzio. By 15 November, the campaign was forced to halt for the winter.

In the meantime, 25,000 soldiers and civilians were killed.

Monty’s men, fighting their way up from the toe of Italy, met with stiff opposition and failed to re-join Clark’s troops until 16 th September. The Germans fought as if possessed, and managed to delay the Allies until reinforcements arrived. 165,000 Brits and Americans arrived on 500 ships, expecting the German forces to swiftly fold however, a feint attack on Taranto, designed to draw the Germans away from the landing site, failed. On 9 th September the Salerno landings- the ones that General Clark expected to take just three days (although Monty was more realistic)- kicked off. Surely the country would fall in no time now? Their elation did not mentally prepare them for the body blow that was shortly to hit them. Italy had officially switched sides in the war.

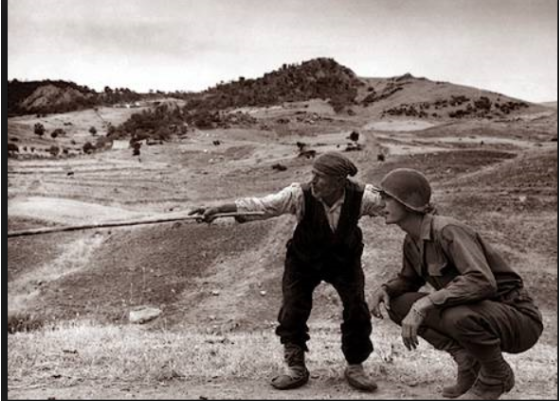

On Sunday 15th August the new leader sent a peace emissary to Spain, and on 3 rd September, as the 8 th Army made their way from the straights of Messina to land in Calabria to launch their invasion of Italy proper, an armistice was signed. On 25 th July the dictator Mussolini was toppled and arrested, and Marshal Badoglia took over as Prime Minister. Ironically, the next threat to the Allied campaign came in the shape of a victory. General Eisenhower later wrote in ‘D Day to VE Day’, his account of the invasion of Europe 1944-45 included in ‘The World War II Collection’, ‘I had felt when I originally read the Overlord plan that our experiences in the Sicilian campaign were being misrepresented, for, while that operation was in most respects successful, it was my conviction that had a larger assault force been employed against the island beachheads our troops would have been in a position to overrun the defences more quickly.’ 40,000 Germans slipped through the net and escaped to fight another day. Although the island was successfully captured by 17 th August, the trap ultimately failed to spring. The plan was for General Montgomery and the British 8 th Army to mount one assault, while General Patten led the US 7 th Army in another, neatly trapping the German army in a pincer movement. The fact that the initial assault on Sicily was so much harder than expected should have rung alarm bells. Despite the Allied victory in North Africa, Germany stubbornly refused to crumble. According to ‘Witness to World War II: an Illustrated Chronicle of the Struggle for Victory’ by Karen Farrington, Churchill labelled the Italian Peninsula as ‘the soft underbelly’ of the Third Reich, while US Commander General Mark Clark allowed just three days from the 9 th September landings at Salerno to the capture of Naples and its harbour in his preliminary battle plan (this objective took 21 days to achieve in practice). Compared with the invasion of France, the difficulties of an assault on Italy were woefully underestimated by many of the Allied troop and leaders.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)